It’s been a big year for Ecuador’s mining sector. The country’s government declared mining to be a pillar of the country’s economy by 2021. It also approved several fiscal and legal reforms that will improve Ecuador’s competitiveness in the global mining industry.

It appears that Ecuador’s government is listening to the greater voice of the mining sector.

Yet, both the Ecuadorian government and Ministry of Mining appear to be passive when it comes to acknowledging the voices of Ecuador’s Indigenous communities.

The year 2021 is right around the corner, and if the voices of Ecuador’s Indigenous populations continue to be ignored, this newfound pillar of Ecuador’s economy will be established on an increasingly unpredictable foundation.

To avoid this, we need to understand the current conversation between mining companies, governments, and Indigenous communities within Ecuador.

Ecuador is one of the first countries to acknowledge nature’s rights in their constitution. With this acknowledgement, it indicates that Indigenous communities must be consulted before any extraction projects happen near or on their land. It is critical to recognize that despite these constitutional requirements, compliance is rare.

The conversation is fluid between the government and the mining corporations involved. However, when it comes to Indigenous populations, the conversation appears to be one-sided.

This push communication metric truly highlights the evident disconnect that exists between constitutional guarantees and reality, not only in Ecuador, but throughout the Americas.

Currently, Ecuador’s indigenous populations are being told what is happening with their land, rather than consulted as is clearly laid out in the constitution, and resistance to mining production is increasing as a result.

Ecuador’s Indigenous Shuar leader Katan told Mongabay News that Ecuador’s constitution was: “the best constitution in the world, but the worst constitution in its application in daily life."

The realities of the inadequate application of their constitution can be highlighted in the eviction of the Shuar Nankint’s community. They were evicted from their land after the Ecuadorian government supported a large-scale copper mine project owned by the Chinese company EXSA. There was no prior consultation before this eviction occurred. Since then, there have been numerous cases of conflict such as the Nankint’s 24 hour take over of the mining camp La Esperanza and the death of police officer José Mejía.

Mining companies need to stop relying on governments to communicate with affected indigenous populations if they want to avoid conflict and costly delays in production. Obviously, it is not a mining company’s role to change the political landscape of the countries they operate in. By avoiding a ‘leave it to the government’ mentality, however, they can build their own relationships with Indigenous groups, which would be both positive and proactive for both sides.

This raises an important question for mining corporations: is there an expectation for the relationship between mining corporations and Indigenous populations to be a direct one? Legally (for now) the answer is no. Despite this, mining corporations may want to start thinking about opening these lines of communication with Indigenous populations sooner rather than later.

When discussing Ecuador’s CSR case with Dr. Chris Anderson, the Principal of Yirri Global, he expressed that Indigenous populations do not have a starting goal of impeding mining production and do not immediately take the stance against development. On the contrary, most Indigenous populations are in favor of development if the following three conditions are met:

1. Their right to free prior and informed consent (FPIC) has been respected and fulfilled.

2. Environmental Protection is included in production plans. This protection plan, however, must be in line with what the indigenous believe to be as protection, not the mining companies definition of environmental protection, so the project will not risk land use for future generations

3. They want themselves, their children and grandchildren to benefit from the extractive activity.

Where governments struggle to make decisions, companies can work towards managing risks and uncertainties. Without a consultation process, mining corporations are going to increasingly find themselves at the forefront of conflict between the local populations and their governments, not only in Ecuador, but on a world scale.

Mining corporations need to be aware that if they fail to consult and engage with impacted Indigenous populations they could experience a myriad of dangerous and costly consequences such as:

- Loss of life and increased violence

- Mine strikes and delays

- Loss in Investor confidence

- Lengthy and costly legal disputes

- Diminished reputation on a global scale

- Increased Environmental damage

The good news is there are plenty of ways mining companies can avoid these consequences and many stem from effective communication strategies to support their corporate social responsibilities, which includes strategic engagement and listening, not just ‘push communication’..

Thanks to globalization, mining corporations are not the only ones that can influence on a global scale. Environmental and corporate watchdog groups are also rapidly expanding and becoming more active. With this expansion comes opportunity for mining corporations to collaborate with various NGOs and communication and engagement specialists to help build their credibility and transparency in the industry. There are benefits for both mining companies and Indigenous populations with these types of partnerships.

An example that speaks to the benefits of partnerships between mining companies and indigenous/ local populations would be Newmont Mining Corporation’s Ahafo facility in North Central Ghana. In his article “Unearthing gold not conflict,” Dr. Anderson writes that this facility is one of the most successful large-scale gold projects, thanks to the partnerships Newmont built with the local communities.

The overall benefit speaks for itself: a mine whose start-up time and expenses were no different from other projects of its size, but whose operations have never lost a day of work because of community unrest, vandalism, or violence.

Dr. Anderson noted that “proper due diligence and risk management undertaken by all companies involved in international land transactions, must incorporate respect for these rights into their business plans, regardless of any government mandate."

It does not need to be some elaborate plan that only a rocket scientist could decipher, but it does need a certain level of expertise to execute effectively. Dr. Anderson explained that it ultimately comes down to acknowledging the land title and ownership of the indigenous communities and respecting it. By building these partnerships with those who have the necessary skill sets, mining companies can have a positive impact on the communities they operate in, while saving money.

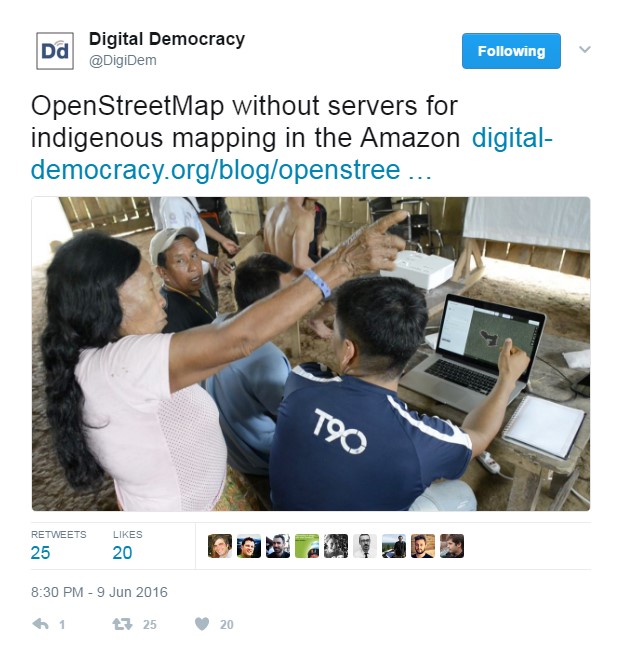

For example, to fight back against various oil companies, the NGO ‘Digital Democracy’ taught Ecuador’s Waorani how to use various technologies such as computers, drones, and GPS systems; equipping them with necessary skills so they could fight to protect their land.

Who was the key player in all this? The answer was the tenacious Waorani and their eagerness to learn.

By giving the Waorani access to technology, Digital Democracy has built trust and provided the Waorani with the tools so that they could understand and influence decisions that involve their land. Unfortunately, mining and oil companies, played zero role in this partnership and formation of trust.

Digital Democracy’s main goal is to: “Empower marginalized communities to use technology to defend their rights.” This is something we are increasingly going to be seeing amongst Indigenous groups all over the world. The Waorani being a prime example of this.

More Indigenous land claims are starting to be recognized and groups like Digital Democracy make it clear that if mining companies are not going to recognize and respect Indigenous rights and title of the lands they want to operate on, then other corporate watchdog groups are going step in. When that happens, mining companies forfeit an opportunity for teamwork and partnership and risk having these groups work against, rather than with the projects they hope to implement.

Mining companies in Ecuador and beyond can take an approach such as Newmont’s or Digital Democracy’s with regards to working together with Indigenous populations. Rather than equipping them to go against mining production, mining companies can raise their capacities with education, and training opportunities that will provide economic benefits such as employment.

Mining companies would be wise not to wait for the Ecuadorian government to apologize on their behalf and should construct a plan of action that ensures they are working in good faith and are engaging respectively with these effected Indigenous communities.

Mining executives need to learn from the past and understand that they do not need to go about their communication and CSR plans alone. Instead, mining companies can strive to enter partnerships with industry experts to help them construct mechanisms for regular discussions and who can assist in improving their credibility on a global scale.

In a statement for Mongabay news, Ecuador’s NGO Amazon Watch’s field coordinator, Carlos Mazabanda, noted that the mining industry has been connected to alleviating Ecuador’s poverty thanks to mining and oil’s funding for various social programs. He states that “you cannot choose which rights you want to comply with and which ones not to.”

As a society, we need mining in order to function as we do, but we also need to strive for a standard where mining companies can inspire and educate the Indigenous populations where their projects operate and prosper while co-existing with Indigenous communities and their land. It appears that in Ecuador, mining companies are going to need to play a bit of catch-up to remediate the wrong doings that have occurred in the past as they slowly strive to build a sense of trust with Ecuador’s Indigenous populations.

Bianca Zimperi has been working in the mining industry for over two years and after receiving her Certificate in Mining Law through Osgoode Hall Law School in Toronto, Canada she realized that her niche exists where mining and law intertwine. As a result, she will be attending Sussex Law come the Fall for their Graduate LL.B. program in Brighton, England. In 2015, Bianca graduated from Wilfrid Laurier University located in Waterloo, Canada with an Honors Bachelor of Arts degree in Political Science with the Legal Studies Option. In her spare time Bianca enjoys writing, photography, exploring Toronto and spending time with her friends and family.